The philosophical thought of the famous, but now somewhat forgotten, Paul Feyerabend, is rich and complex. This thinker of great culture and great personal experiences has tried to synthesize his understanding of science on the "principle"1 of “anything goes”, that is nothing but the synthesized expression of his dadaism epistemological anarchism. It is in opposition to all forms of absolutism and authoritarianism epistemic and all forms of dogma.

It is epistemological anarchism because

the author proposes to abandon the ideal of positivist rationality,

which still continues the cartesian conception of reason, based on

rules that are believed "certains and infallibles”. This way

of teaching scientific rationality, without passions and without

emotion, is taught as standard in the "scientific method."

For Feyerabend such conception about rationality is cold, useless and

reductionist. And of course, unworthy for a free man.

On this the author makes a very

important observation. Here I quote his words:

“(...) the history of science will be as complex, chaotic, full of mistakes, and entertaining as the ideas it contains, and these ideas in tum will be as complex, chaotic, full of mistakes, and entertaining as are the minds of those who invented them. Conversely, a little brainwashing will go a long way in making the history of science duller, simpler, more uniform, more 'objective' and more easily accessible to treatment by strict and unchangeable rules.

Scientific education as we know it today has precisely this aim. It simplifies 'science' by simplifying its participants: first, a domain of research is defined. The domain is separated from the rest of history (physics, for example, is separated from metaphysics and from theology) and given a 'logic' of its own.” (Feyerabend, 1993: 11)

History of science (e.g. Galileo,

Copernicus and Einstein) shows, according to Feyerabend, that there

is not rules, and that is absolute necesary broke the rules for

the growth of the knowledge. Later the author says in

his classic, "Against Method. Outline of an anarchistic theory

of knowledge" in an ironic and mocking way, that the only

abstract principle that can be defended is the principle of “anything

goes”, which in any case can be the only principle of "anarchist methodology".

It is clear that Feyerabend is far from

proposing a well-defined set of "anti-methods", or

"anti-rules" (standards defined in negative) that we have,

that we must to follow for ensure the "correct" development

of the science. Rather is concerned with the creation of a free and

humanistic attitude, which takes as its central axis the cultivation

of individuality in the intellectual formation of the persons (and

this is the why he does a radical rejection of the trends of

hyper-specialization and standardization of science that have the effect of castration of thought, minds amputated,

objectified, and thus, the dehumanization of people who are trained

in the canons of the modern science hyper-specialized, at service of

the Capital). For this he suggests that scientists should learn art.

For this author the ideal scientist is Galileo Galilei who

represented very well the spirit of the Renaissance: do everything

for to can have an immense creative capacity in all activity (science included). Besides, Galileo Galilei

was for his time a rebel.

In this sense, for Feyerabend both the

"error theory" as "counterinduction"2

are simply heuristic devices that inspire the movement of thought of

scientists depending the specific applications of these in various

and particular episodes in the history of science. These are not mere

"methods" that consist of well-defined steps to follow,

rule or inflexible principles (defined in negative, as everything

that the scientist should not do) that every free thinker and

humanist must follow. Feyerabend simply describes how these resources

have operated in the history of science, that is in the reality very

complex, rich, and fun in many specific episodes. This author does

not try to show these resources as "laws" that operate

always in the historical development of science. So there is nothing

like "recipes" that ensure the full knowledge of reality,

neither that something is true and valid forever.

In this sense, for Feyerabend both the

"error theory" as "counterinduction"2

are simply heuristic devices that inspire the movement of thought of

scientists depending the specific applications of these in various

and particular episodes in the history of science. These are not mere

"methods" that consist of well-defined steps to follow,

rule or inflexible principles (defined in negative, as everything

that the scientist should not do) that every free thinker and

humanist must follow. Feyerabend simply describes how these resources

have operated in the history of science, that is in the reality very

complex, rich, and fun in many specific episodes. This author does

not try to show these resources as "laws" that operate

always in the historical development of science. So there is nothing

like "recipes" that ensure the full knowledge of reality,

neither that something is true and valid forever.

In this sense, Feyerabend, rather than

worrying about proposing a new "methodology" that must be

followed by everybody, focuses on highlighting the heuristics of

science that are inside and outside academia and forms free and human

thoughts. From here he does a defense of pluralism that was proposed

by the liberal philosopher (and socialist too) of the nineteenth

century, John Stuart Mill, in his classic book "On Liberty".

Feyerabend attaches great importance to this book, the other author

on which he supports his ideas is Hegel, as we shall see3.

The proliferation, diversity and

tolerance (in clear analogy with John Stuart Mill) are sources of

heuristics that can be useful for scientists who must not be

repressed or censored at all, otherwise they will have less choice

options and confrontation of ideas. Thus Feyerabend considers that

while more plurality there are, it is more chance to promote the

advancement of science through contrasts of different ideas, often

antagonistic to each other. So in schools should be taught more than

a single standardized view of science, which tends to limit the

imagination of scientists, and thus the progress of science.

Education should be radically plural. Here is the point where

dialectic occupies an important place in Feyerabend's philosophy. In

fact this point tend to be forgotten when we are discussing

Feyerabend's ideas, which has been criticized many times only

considering his pluralism in a partial way. If we stay only with the

Mill's perspective would be very limited and, if you want,

reactionary, so “plurality” in the academies can become in mutual

indifference. This can be an example of feudalisation of knowledge.

Let's see what the misunderstood Feyerabend said about the topic.

The authors that Feyerabend takes for

build a picture of the dialectic that lets him connect the "principle

of proliferation" and "epistemic pluralism" with their

particular notion of scientific progress (understood as a process of

conceptual enrichment) are Georg Hegel (mainly), Friedrich Engels,

Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong. He supports his ideas critically on

them (highlighting only the elements "anarchists" of

thought of these intellectuals) to explain as best as possible the

three principles (laws) "universals" on dialectics that

were exposed by hegel. This principles should be present in the

thought of all genuine scientists always open to criticism and the

progressive changes of knowledge. These are as follows:

a) The consideration that all parts of

a whole are bound together, because each part, in turn, are

self-contained and contains the whole. That is, each part contains

what it is and what it is not;

b) All finite objects in its historical

development are in a struggle for being what they are not. This

antagonism keeps in constant tension with the various parts that

constitute the whole of nature, so that when the object moves beyond

the limits of what it is, the object ceases to be what it is and it

becomes in what is not. Is "negated" and in this sense a

movement is generated (in the aristotelian sense of the term, not in

the newtonian sense) both in nature and in human thought;

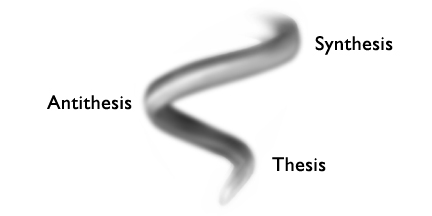

c) The negation, both in concept and in

fact, results in a "special" content that express a new

"higher" and "richer" concept than before. This

is because it has been enriched by its negation, being the unit of

the original concept and its opposition. We are in what is often

called "affirmation of negation" or simply as "synthesis"

temporary culmination of the confrontation between the "affirmation"

(thesis) and "negation" (antithesis), but contains both of

them, in turn is the negation of them. So it becomes in the new

starting point of the dialectical movement of nature.

These three principles of dialectic are

taken by Feyerabend for show the importance of the interaction

between ideas (even antagonistic) and thus show how important is the

change in scientific concepts (which are all finite like man). In

this sense, for Feyerabend the conceptual stagnation of science (and

any tradition of thought, which indeed can been considered ORTHODOX)

far from being a success represents a failure, simply because

it is not dialectical (just like the currently case of the orthodox

economic thinking that is taught in a dominant and privileged way in

many parts of the world and now is unable to give practical answers

to the current global economic crisis).

In this sense I found in Feyerabend a

position clearly progressive with respect to science (because he

promotes its constantly transformation), acknowledging the

possibility of the existence of acumulative progress, but as in

Hegel, neither linear and fatally determined. He would say that the

dialogue between the various positions should be frank, open and

fluid, and in this sense I think he would criticize those positions

that favor their prejudices in a dialogue and confrontation with the

diverse (the strange, the other) for maintain their conservative

positions.

In this sense, Feyerabend's

epistemological thinking (which has clearly subversive consequences,

because it tends to encourage a critical attitude very radicalized,

almost skeptical, naturally antagonistic to all conservatism and the

currect status quo, which results in the thesis that I

support: all orthodoxy is anachronistic and dogmatic) can not

be understood without considering their ontological bases clearly

dialecticals. This bases are the most universals that can be and are

useful to him, because let him support his epistemic pluralism in a

stronger and better way. In this sense, no censorship of ideas also

plays a role in the evolution of the right ideas, according to Mao

Zedong, who claims that the right ideas fight againts the bad ideas

to prevail in the minds of people and this contrast is useful for

note the differences between them. This process allows that the right

ideas get imposed with more force and liveliness against those ideas

that are considered “wrong” by some pleople. Nevertheless, those

who defend these “wrong ideas” also have the right to refuse to

accept the "right ideas” and keep working on the first ones

for transform them and keep inside the debate epistemic on how the

world really is. In this sense, pluralism and proliferation benefit

to all of us as long as nobody have conservative and dogmatic

attitudes that manifest in a strong opposition to all critics without

give arguments and without the will for to change the ideas claimed.

It must be said, finally, that

Feyerabend does not postulate and promotes epistemic relativism in a

strictly point of view (which claim that any theory and any statement

about the world is valid), precisely because their bases of thinking

are dialecticals. This led him to affirm that the main task of all

genuine intellectual is achieve identity between thing and concept. It's like Lenin says about knowledge:

"Human knowledge is not (or does not follow) a straight line, but a curve, which endlessly approximates a series of circles, a spiral. Any fragment, segment, section of this curve can be transformed (transformed one-sidedly) into an independent, complete, straight line, which then (if one does not see the wood for the trees) leads into the quagmire, into clerical obscurantism (where it is anchored by the class interests of the ruling classes). Rectilinearity and one-sidedness, woodenness and petrification, subjectivism and subjective blindness—voilà the epistemological roots of idealism." (See his notes "On the question of dialectics")

That is why the "counterinduction" of Feyerabend is not a rule, but simply a resource, like any other, that the

genuine scientific can use in his practices for achieve a better

understanding of the world and for change it.

Bibliography

Feyerabend Paul

(1993), Against method. Outline of an anarchistic theory of

knowledge, Third Edition, ED New Left books, Great Britain London

______________

(1981), “Two models of epistemic change: Mill and Hegel” in

Problems of empiricism Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press

Lenin Vladimir (1976), "On the question of dialectics", in Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th Edition, Moscow, Volume 38

1 Actually for Feyerabend this “principle” is more a "medicine"

that can be very useful for the scientific thought.

2

This consist, particularly in the natural sciences, in not always

take as valid the "empirical evidence" that are skewing

the object study by the use of statistical and equipment for

research. These will not guarantee forever that something is true or

false in a conclusively way, as discussed from the time of Pierre

Duhem and later with Hanson in classic problems as "empirical

underdetermination of theory by evidence" and "theory-laden

of observation".

3

I'm referring the Feyerabend's article called “Two models of

epistemic change”.